How does the socioeconomic environment of a Founder’s childhood shape their attitudes to risk and reward, their hunger, drive and passion to perform?

How does risk appetite and performance differ as a Founder grows wealthier?

Are allocators correct to prefer a larger amount of personal wealth invested in the fund as a proxy for success and aligned interests?

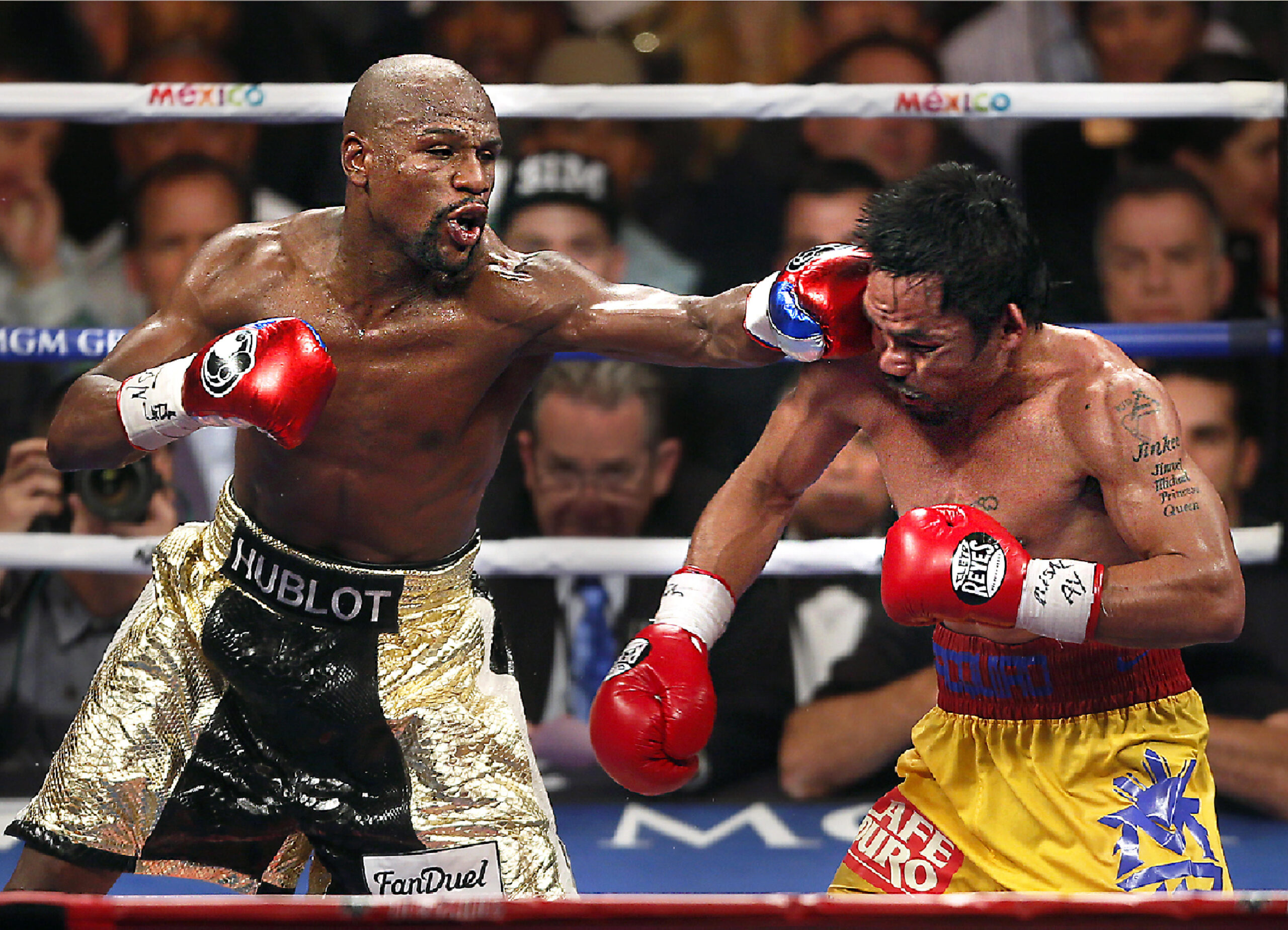

“When people see what I have now, they have no idea of where I came from and how I didn’t have anything growing up…even though I made $800 million, I am still grounded”

Floyd ‘Money’ Mayweather, Jr.

Sports stars often attribute motivation in the early parts of their career to their humble backgrounds. For those successful enough to amass significant wealth, their hunger and drive is often questioned later in their career: they have less to gain, and less to prove. In this Research Note, Stable explores this phenomenon in the world of asset management.

Founders are more likely to come from wealthier backgrounds: research has found that the median value of a Founder’s childhood home was 2.5x greater than state averages1. However, from a performance perspective, the same study found that Founders whose parents were from the least wealthy quintile outperformed those from the wealthiest quintile by over 1% per year. The popular explanation for this is that those from the least wealthy backgrounds had to work the hardest and demonstrate greater ability than their wealthier counterparts to get into the world of asset management. Therefore, there is a quality bias: only the smartest and hardest working individuals from poorer backgrounds become asset managers, whereas there is a wider spectrum of ability and drive amongst asset managers from wealthier backgrounds. This echoes the popular explanation for the outperformance of female managers outlined in our piece on Gender. This explanation was supported by the finding that those from poorer backgrounds had to perform better to be promoted than those from wealthier backgrounds.

It is worth noting that the empirical evidence cited above was based on mutual fund managers – and so caution must be taken when generalizing between the type of asset management firm given varied incentive structures across the industry, as we saw in our “Youth” Research Note. However, when selecting our Partnerships, we pay close attention to what drives potential Founders to perform. We analyze incentives of all kinds and have found many allocators underestimate the role non-financial incentives play compared to financial incentives. Incentives may differ for Founders of different wealth levels. Appetites and aversions to risk do not follow a linear utility function. Specifically, it may be that less wealthy Founders are more incentivized to return, or that wealthier Founders are incentivized not to lose what they already have.

Studies show that when the amount of money at stake is higher, and potential gains and losses become larger, individuals become more risk averse despite the same odds. Crucially, it is when the amount of money at stake is higher on a dollar basis, not on a relative percentage basis. Theoretically, this is because each additional unit of profits has less utility than the last; and each unit of losses has more utility than the last – a concave relationship. When stakes are higher, individuals become more risk averse.

This has profound implications on the asset management industry: it would dictate that on average Founders who are wealthier and have more personal capital at risk will likely take less risk and underperform. Data specific to alternative asset managers supports this: smaller funds outperform. Wealthier managers want to remain wealthy, smaller, less wealthy managers want to become wealthy (by performing!).

What therefore is the optimal amount of wealth for a Founder to have? Should allocators prefer a larger figure when a Founder is asked how much ‘skin in the game’ they have? Obviously, greater risk appetite and motivation needs to be balanced with commercial and common-sense considerations: personal wealth (if acquired from investment performance) is an indicator of success as well as track record quality and shows that interests between an asset-owner and a Founder are more aligned. There is obviously no correct answer, but it is more of a balanced debate than the common one-sided belief that the more personal wealth invested in the fund the better. We believe that the most relevant measure is what proportion of a Founder’s wealth is invested in the fund, not necessarily the amount. We want the investment to be as large a percent as possible, whilst allowing for some cash buffer so a Founder is unlikely to need to take money out of the fund and be able to reinvest the majority of their performance fee.

At Stable we take time to understand all aspects of a Founder’s background, including their childhood background and current wealth levels. Whilst a Founder from a poorer background may statistically be more likely to outperform compared to a Founder from a wealthy background if selected randomly, we do not proactively favor those from poorer backgrounds. We do however think about the role of wealth in a Founder’s motivation to help us improve our due diligence process. For instance, we would spend more time assessing a Founder’s motivation, drive and risk appetite if they had $1B in the bank; and likewise, would spend more time understanding a Founder’s prior track record if they had very little acquired wealth to show for it. Great Founders are incentivized by a passion for what they do. The thrill of competing and winning can often be a large source of motivation. One has to distinguish true passion for excellence from a thirst for status and recognition. Generating wealth for most is a welcome side-effect, but they would probably still do what they do even if asset management was a less lucrative profession.

- Chuprinin & Sosyura, 2016, “Family Descent as a Signal of Managerial Quality: Evidence from Mutual Funds”

- Friedman, Milton & Savage, 1948, “Utility Analysis of Choices Involving Risk”

- Holt & Laury, 2002, “Risk Aversion and Incentive Effects”

- Markowtiz 1952, “The Utility of Wealth”

- Preqin Spotlight: June 2017